Let's talk about Wannacry, where it came from and how it grew to be big enough to take down the NHS for a few days. I've got a store now too! check it out! Store Link: https://store.whattheshellpod.com

Since the very first episode, I've talked off and on at points about ransomware and the big problems they can cause. In fact, we already talked a bit about this one piece of ransomware called Wannacry\ back in earlier episodes but I think it deserves it's own full episode given the scope of it all from start to finish. You probably remember it as that big virus that took down the National Health Service. I'm John Kordis and today I'm going to take you back to 2017, and we're going talk about What the Shell Wannacry is. But more importantly, we're going to take you back to how it was able to make as a big an impact as it did, by exploring what helped it propagate it's way across the internet.

Intro Plays

Before we get into the episode I want to take a quick second to tell you about something exciting. If you follow me on instagram you might have seen me posting that I've gone ahead and tested some items from an online store that I was hoping I could offer you. Well it's here. If you want a "What the Shell" T-Shirt, hat, sticker, or patch you can get one at store.whattheshellpod.com. I did my best to try and offer something that I'd wear out, in both the traditional logo and the wireless rebellion logo for the show. So, if that's something you'd be interested in go ahead and take a look. That's store.whattheshellpod.com or just follow the link I'm going to put in the description.

So I know I just said we're going to talk about Wannacry. But to do that well.. we need to understand the lead up to it and how all the pieces came together in a perfect storm of disaster. We know that the Wannacry was the product of the Lazarus group. That group being an advanced persistent threat, or APT, that operates out of North Korea. Their primary goals seem to be state sponsored cyber espionage, and attacks that will make money for the North Korean government. If you want to know a lot more about them and their inner workings I have an entire episode on them you can listen to.

So now you have a good enough idea of the 'who' of it. Let's take a step back again and give a little bit of a recap of what ransomware actually is. You've all probably heard of it in one way or another at this point. It would be pretty hard to ignore given just how many different kinds of ransomware there are and how often they tend to make the news. To put it simply, ransomware is a piece of malware that will encrypt every file on your computer or file share. Only the people who control the ransomware have the decryption key for this, so what do they do? They hold it hostage. Typically, this means that accompanying the encryption of your files, you'll see a note demanding some form of payment, likely in a cryptocurrency such as bitcoin, in exchange for the key to decrypt your files.

An analogy for this might be like a thief breaking into your house while you're gone. Only, instead of just stealing the contents of your house he decided to lock every door and window with keys that only he had. And when you got home, there would be a note taped to the front saying to leave some cash in exchange for the new keys to get in.

In both situations you have two options. You can either abandon the computer, or house as it were, and start over with a blank slate. This might seem like it's a bit overkill, but let's talk about the second option before we jump to that point. The second option is that you pay off the criminal and they give you the keys. The big fear here is that you need to be 100% certain that you know how they got in, that they're not still there somewhere you haven't looked, and that they'll actually hold up their end of the bargain after you pay them. These are criminals we're dealing with after all, so it's not surprising to know that sometimes they'll come back and re-encrypt your files, keep a foothold in your network, or just lie and take your money.

There is a bit of a third option that lies between those two but that requires you have a responsible and capable Information Security program. The last option is backups. A backup is a snapshot of the device as it was in a specific point in time. A lot of programs will capture this weekly, meaning that if you can find out when the attacker got in, you could theoretically backup to just before then and only lose the gap between then and now. Not every program has a solid backup procedure, and this requires a lot of care and attention, but it's probably the best method to ensure you're not just replacing a whole of computers and starting from scratch.

Just a minute ago I talked about how you need to make sure the attacker is gone from your network. That's because ransomware is just a part of the formula that results in the payout. There's still the matter of the initial break in, so to speak. A hacker or hacking group needs an exploit to let them in and start the whole process.

There's a whole market revolving around these exploits. Hackers and researchers will spend countless hours looking at code and systems trying to find ways they could wriggle their way in or ways to escalate their permissions from a normal user into an admin level access. If you're doing this legally, they are often referred to as bug bounties. Many companies have specific test criteria and will pay you out if you find a bug in their tools. One of the first companies that did this was actually netscape, the dial up internet platform way back in 1995. It caught on a lot more in the mid 00's and now there's thousands of companies doing this.

Why though? Well, in some cases it can be more cost effective. The cost of essentially outsourcing security for that vulnerability and paying out the hacker who found it so that you can patch it is likely less than the repercussions. Not only would you potentially have a fiscal loss in the way of fines, machine replacement, and man hours…but the company would have a reputational loss if that same weakness was exploited by someone looking to do damage or get a bigger payout. Just last year, google paid one researcher $157,000 after they found a major security issue in the Android OS.

The thing you need to understand here though is that this was in the upper echelon of payouts. So, that's not the norm at all. The average bug bounty payout according to popsci.com is just 250 dollars. Obviously the lower cost vulnerabilities were likely easier to find and less time consuming but that's the range we're working with here if you're going about things legally speaking.

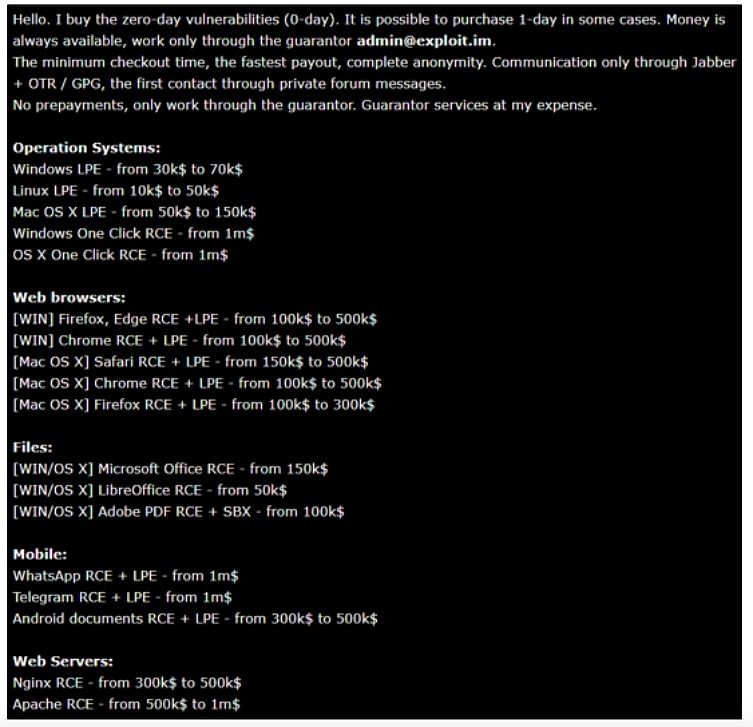

But, there's other groups willing to pay even more for exploits that haven't been revealed. This group consists of criminals and even nation states like the US, China, Russia, and North Korea. These groups can get away with payouts that are orders of magnitude greater than their corporate counterparts. Why? Well, just think about it. If someone posts on the darkweb that they have an exploit against a popular operating system or tool that hasn't been patched anywhere yet, what could an intelligence agency do with that kind of power? That's why if you're on the darkweb you'll often see notes that read like this: (as a sidebar, I'll have this note attached on my website in the transcript at whattheshellpodcast.com

Hello. I buy the zero-day vulnerabilities. It is possible to purchase 1-day in some cases. Money is always available.

It goes on to list some of the payouts. For example an Operating system vulnerability that lets you go from a normal user to an admin would get you between 30 and 70 thousand for windows, 10 and fifty thousand for linux, and 50 to 150 thousand for Mac OS's. These are on the lower end of payouts because to escalate privileges you already need to be on the network, usually with the credentials you've gotten through phishing or other means.

For an easy to use exploit that let's you actually run commands right off the bat? Well those will pay up to 1 million. Those are just the operating systems though, Browser hacks are being offered from 100k to half a mil and there are payout offers for mobile apps as well. I encourage you to take a look at it on the website.

So it's no surprise that in a lot of places hackers decide to go the less than legal route when you see payouts like that. If you take it a step back though, it's also no surprise that many countries don't necessarily want to only do payouts and instead have their own teams of exploit researchers that will try to poke holes where ever they can and use those to their advantage.

I want to pause here. Because surely you're wondering where Wannacry is at this point. And don't worry it's coming. There's just a few more pieces that we need to set down to get to that.

So let's step back into 2016 because one hacker group, dubbed The Shadow Brokers, decided they had stuff that was worth the payout. In fact, they claimed that they had "the best cyberweapons" made by the United States, in fact by the NSA. In a release hoping to get them a payout of 1 million bitcoin, 568 million dollars at that time, they said the following:

"We follow Equation Group traffic," "We find Equation Group source range. We hack Equation Group. We find many many Equation Group cyber weapons. You see pictures. We give you some Equation Group files free, you see. This is good proof no? You enjoy!!! You break many things. You find many intrusions. You write many words. But not all, we are auction the best files."

The Equation group had a reputation as one of, if not the top, Advanced threat actors out there. And the leak here? Well it contained exploits for both American and Chinese firewalls. Researchers were quick to respond, many stating that this looked incredibly legitimate.

Over the coming months, August into early December, several of the companies impacted confirmed that these were unpatched vulnerabilities in their hardware. The Shadowbrokers had their hands on incredibly valuable stuff for sure and to give even more credence to the idea that this was all the NSA's tools and not just them playing around pointing fingers, they released a list of foreign servers allegedly compromised by the NSA as of Halloween 2016.

When the auction failed to get what they wanted out of it, they started just straight selling the exploits on underground sites. Things came to a head with regard to our story on April 8th, 2017.

On that date, the Shadowbrokers dumped a myriad of exploits to their github. I've got the github linked in the transcript so you can actually go ahead and take a look at them. If you want.

https://github.com/misterch0c/shadowbroker

There were a lot, and I mean a lot, of valuable and notable exploits here but there's only one we want. The key to making Wannacry work. And that exploit was called Eternal Blue. That.....was the entry point, the way the thief could break into your house, the starting point for how things would snowball into full blown chaos.

Eternal Blue was an exploit that used a very common windows protocol in a way that allowed nearly full control over the host system if exploited correctly. That protocol was called SMBv1, or Server Message Block. It was developed in the early 80s as a way to easily share files across the network using a dedicated port. It does that by negotiating a connection between the client and the server that is being accessed and communicating a request on the designated port. Well, here is where the exploit would insert itself. Under certain conditions a malicious version of those request packets would be processed and allowed, resulting in the attacker being able to connect to the system and start getting to work spreading their malware… in this case, it would end up resulting in the spread of a ransomware.

What's interesting here is that just one month before this, Microsoft released a patch for this very issue. To the security industry at large, this suggested even more legitimacy that the exploits which would be released were tied to the United States. It was suggested that the NSA, in an attempt to curb exploitation, alerted Microsoft of the issue so they could patch it before it got out as a part of the Shadowbrokers leak. I guess the mentality here was a bit of mutually assured non-destruction. If this was going to get out into the world, the NSA would rather cut their own limb off here and no longer be able to use the exploit that they'd likely been using for quite a while.

Either way, this is exactly what someone was waiting for to use to chain something dangerous too. Enter, the Lazarus group. We've talked about them before, and if you're interested I'd suggest you go back and listen to the Sony episode and the Lazarus episodes that I've done. Long story short, they're a state sponsored hacking affiliate to North Korea.

So, in the month since the shadowbrokers dumped the exploit pack, the Lazarus group took the an early iteration of the WannaCry ransomware, combined the two and boom. Now we've got a catastrophe on our hands.

There was a catch though. The eternal blue exploit primarily worked on older systems of Windows, well what's now older systems anyways. Wannacry had to use early versions Windows 7 and even some Windows XP systems to move around, and fortunately for the Lazarus group those were plenty of those around in 2017. According to statista, just 35% or so of systems had been updated to Windows 10 at that point, it having been out only two years. That left 65% of the windows market or so to be targeted.

And here's the thing, there's no user interaction to get this started. You just need to be able to see the computer on your network. So if you look at the internet right now, as it stands, there are over 5 million Windows systems directly attached. I'm using a tool called shodan to look this up, it's a company that provides open source intelligence based on their scanning of what's on the internet. If I break it down further, there are 600,000 with the SMB port open to the internet as well, you know the port of the service that's vulnerable here? That's a hefty amount of targets to just start spamming with an attack and even if just 1% of the machines responded and were hit, that's 6,000 machines that I can now use as a foothold into the network and then start going after everything that isn't connected to the internet.

Where did this hit the most heavily? You probably remember, even if you didn't know the full context of it. It hit the most heavily in the National Healthcare System for the UK.

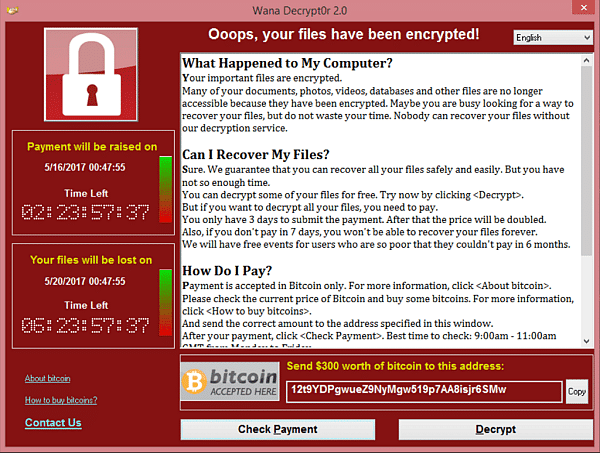

The first sightings of something amiss happened just after 3 In the morning Eastern time, 8 in the morning London time. Several institutions were reporting that they were getting locked out of their files. Among them, the NHS which was specifically seeing computers being blocked, access to patient files being lost, and certain machines losing the ability to operate. If you walked in as an employee of the NHS you probably saw a red window on your machine with the ransomware message. This, again, will be on the transcript on the website.

It read

"Oops, your files have been encrypted". and went on to offer some polite insight into what happened in the form of a simple FAQ section. It answered what happened, explaining that everything was locked and they had the keys, it offered the solution to getting the keys, in this case paying 300 dollars in bitcoin, and then it offered some instructions on how to pay it. Then, on the left it explained that there was a time limit of 3 days before the price doubled and 7 days before the files were just deleted. No recovery, do not pass go, do not collect 200 dollars.

A small saving grace that some users might have noticed was that instead of this ransomware message, they were greeted with a blue screen. That's because Eternal Blue had some issues on the newer versions of Windows at the time, and instead of propagating and running the code that was built for this, the computer just crashed. Honestly, it was probably the only time in an IT persons life they'd be relieved to have a blue screen of death show up.

And You might be thinking to yourself, how many machines could that possibly have been? In 2017 windows 10 had been out for about 2 years by that point, so you'd think that people would have had time to update.

Well…that isn't always the case. I worked in healthcare cyber security for about five years. There's a lot you need to consider when trying to upgrade something. For instance, if you take a server or station down, are you going to stop any programs running for patients? What if the upgrade breaks those tools? A lot of healthcare software can be years old because the hardware it works in conjunction with is equally as old and it's just difficult to find the time and money to update it without impacting a litany of hospital resources. So what happens instead? The risk is accepted and people keep going on about the day, until something knocks the service over and you're forced to update it.

This lasaize (find proper) faire mentality happens far beyond just hospital infrastructure, but unfortunately for the NHS this was they were the big fish of the day. All in all upwards of 300,000 devices were hit with the ransomware. In the UK alone, about 20,000 appointments needed to be canceled and it's estimated that it cost the NHS about 92 million pounds.

It got so bad that 3 days later the NHS was still using primarily paper documents, needing to abandon the digital format that had become standard at that point.

So how did this stop? How did we get a bit of light at the end of the tunnel here? Well, I'm going to kick over to one security researcher by the name of Marcus Hutchins, because he is the one that figured out something pretty weird was happening behind the scenes of the attack.

So, after lunch on that Friday, Marcus got home and noticed on the threat sharing platform he used that it was flooded with news of the wannacry impact on the NHS. In an article he wrote about the situation he said quote:

"Although ransomware on a public sector system isn’t even newsworthy, systems being hit simultaneously across the country is (contrary to popular belief, most NHS employees don’t open phishing emails which suggested that something to be this widespread it would have to be propagated using another method)"

As the day went on, he was able to get a sample of the malware and started to reverse engineer it a bit, only to find that it was calling out to a specific domain. That, in and of itself is not unusual. Pretty frequently malware will reach back to what is called a command and control domain. That's basically a server owned by the attacker that can perform a multitude of functions, including receive loot, give new instructions, and other things that genuinely should concern your cyber defense team.

But, what was weird here, is that this domain was unregistered. Every website that has a domain name like facebook, google, youtube, they all have that name registered and in control. Marcus noted that this, was unregistered….so he decided to register it. It wasn't the first time he'd done something like that either. It's a pretty common thing to think about, how can you maintain leverage over or track the potential c2 server. So, he didn't think much of that at the time, but he was able to use tools to detect that this attack started at around 8AM London time given the amount of queries going to that domain.

While that went on, he continued to note look at the malware and had made the leap in his head that based on the connections he was seeing it try to make, that this could have been using the eternalblue exploit from a month prior. Eventually, he did what I love which is just sourcing his info to the community at large and seeing if anyone else came to similar conclusions.

Researchers at Cisco Talos wanted to try and confirm it so they reached out to Marcus for the sample of the malware he had. Only there was a problem. They couldn't get it to run. The exact same sample he was using was failing now for the new researchers trying to take a look.

It turns out Marcus had accidentally triggered the killswitch for the malware when he registered that domain. To verify that this domain registration was, in fact, the killswitch, he decided to modify his own hosts file so that the domain lookup would purposely fail. This effectively simulated how it was before he registered it. With that set, he anxiously tried to launch the code and low and behold it worked.

It turned out the process for Wannacry to operate was something like this: look for the domain. IF it's not registered, ransom that system and spread. If it is registered, do nothing.

https://www.malwaretech.com/2017/05/how-to-accidentally-stop-a-global-cyber-attacks.html

There were a few other considerations that Marcus had voiced concerns about though. Firstly, was this the only domain? Turned out that yes it was….kind of. It was the only domain for that instance of the Wannacry. But much like another virus I won't name, there are possible variants that might be calling out to a different domain. And it wasn't unreasonable to think that they would just change it and repropagate. It was critical that systems, especially internet facing systems, get patched immediately.

If you're interested in a bit more of a technical dive of this story, Marcus wrote a great blog post titled "How to accidentally stop global cyber attacks". It's a great read.

Wannacry didn't just stop though. It would keep changing and impact more and more institutions. All in all, It would spread to more than 150 countries and when you factor in the other companies it hit, this ransomware did around 4 billion dollars in damages. These damages come from things like missed services that make a profit, insurance paying out the ransom, equipment that needed to be replaced, and all the other little things that happen when you grind to a halt and need to make sure every little thing is clean.

Wannacry was probably one of the first ransomwares to really catch the public eye possibly because of just how far it's reach went. You might think upon reading this that the UK was the holder of the most amount of users hit by it, but it was actually Russia. It took out systems in Russias interior ministry, it's railways, banks, and even some of their cell phone providers.

Here in the united states, it did damage to FedEx, causing delays in deliveries that would total up to hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages.

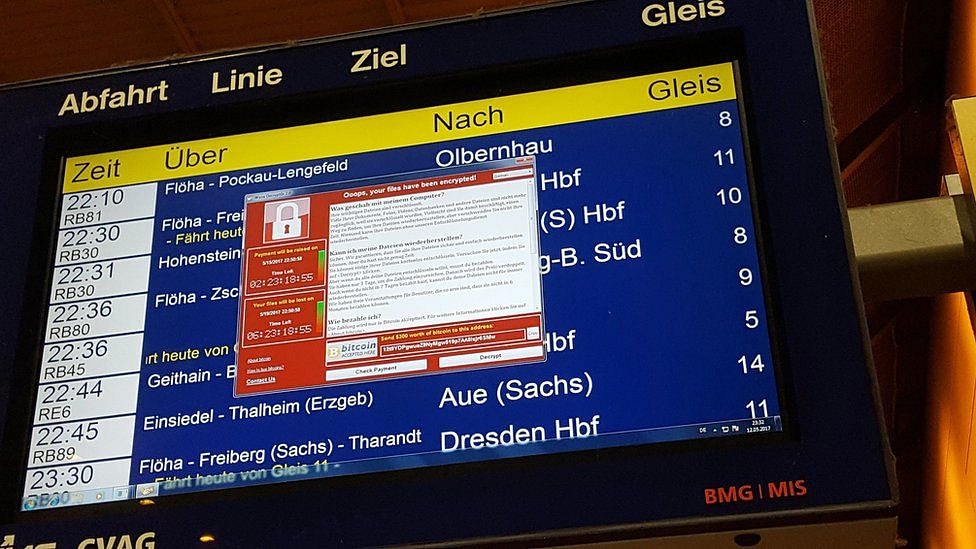

German Railways saw themselves hit with it. So not only were we looking at a potential healthcare disaster here, we were looking at infrastructure problems. I've put a screenshot of one situation where the schedule for the German rail system is cutoff by the wannacry ransom note.

In South Korea, it was the cinema, one of the countries biggest cinema conglomerates said that their advertising servers were hit and it caused impacts at 50 of the cinemas that were connected to those servers.

Even in China, hundreds of thousands of computers were hit with this. That spans roughly 30,000 institutions including government agencies and hospitals.

My point with all of this is that something like this, doesn't really know borders. It didn't stop unless that killswitch had been triggered. And even then, that didn't help all the people and organizations that were already encrypted. Each of those organizations would now have to devote time and resources into a full investigation, a full recovery, and a verification to make sure that it was out of their system once and for all. That is not a simple task, especially for organizations that place restrictions on when events like that can occur. And even after that, whatever work they had been doing was now significantly delayed causing another loss! This is where we see the fiscal cost that isn't much talked about. It adds up fast and from every direction.

Wannacry raised the game for security awareness. The importance of a solid patching program for your systems was critical, because while some industries watched this all unfold scared that they might be next, the ones that maintained a good practice were able to keep up and likely avoid major impact. It raised the standards of the security industry as a whole, which in the end would benefit programs but at that point in time it certainly felt a bit different. I think before this incident there was an attitude that something like this just wasn't likely to happen to your own program. But wannacry certainly knew how to humble an industry.

On the flipside of it, I think wannacry also really showed the black hat hacking community how much of a profit there was to be made in ransomware. It could be pretty easy to set up, and the potential payout was pretty high. So, over the coming years it was unsurprising to see the ransomware attack vector grow in popularity. Even today, some people don't have great patching programs, and there are newer versions of wannacry that continue to operate.

All this happened so that North Korea could make some profit. 300,000 machines, 4 billion in damages, how much money do you think they got away with? Let's start with the ransom note. We saw that they asked for payment in the amount of 300 dollars immediately, and 600 dollars. The ended up, all in all with about 54 bitcoin. Bitcoin is a bit volatile though, so let's take a look.

At the time, if they had withdrawn it immediately they would have had about 120k dollars since bitcoin was at about 2.2k per coin. That year though, bitcoin would start to take off a bit closing the year at around 16k per coin. So if they withdrew in late September of 2017 they could have gotten 864k or so.

To really showcase that volatility, let's look at last episode, which was less than a year ago. Then, it was valued at 61k per coin….so 2 coins alone would have netted them the entirety of the attack. The whole stack? That would fetch a whopping 3.3 million dollars or so.

And lastly, that brings us to today, where bitcoin is worth, as of recording, roughly 30k per coin. Half of what it was last year. There's a lot to unpack about that in and of itself but we won't get into that, so they'd have made out with around 1.55 million if they'd have held on till now.

And yeah it worked, but in the end I don't think they landed net positive because they'd get even more sanctions levied at them. And as for Marcus, he continues to be a pretty prominent security researcher, and runs the site malwaretech. Go take a look. In fact, I'd suggest it because on the next episode I'm going to tell you more about what else he's done beyond this. because as always, there's more to the topic than just this. I'm John Kordis, and thanks for listening to me explain how Wannacry came to be.

Thanks again for listening to this weeks episode. As always, if you liked it please leave a rating or a review. Or, if that's not something you really want to do just recommend it to a friend maybe? I'm still a small show so word of mouth goes a long way. If you want to come and talk to me directly, along with other fans, I've got a link to our discord in the description and on the website. I'd love to have you other there. It's also a great way to just give topic suggestions. If you listened to last weeks trailer, you might have heard me say that this season is going to try to take you, the listener, into account a bit more. The idea for this episode and the Marcus Hutchins episode coming up came from my friend in the UK, Rav. So thanks for that Rav. I had a blast sitting down for this one. And lastly, like I said, I've got a store now, so if you want a sticker for your laptop, a patch for your backpack, or maybe just a T-shirt, go take a look. That's it for today, I'll see you all in two weeks for that talk about Marcus and what his career looks like, because it's pretty interesting.